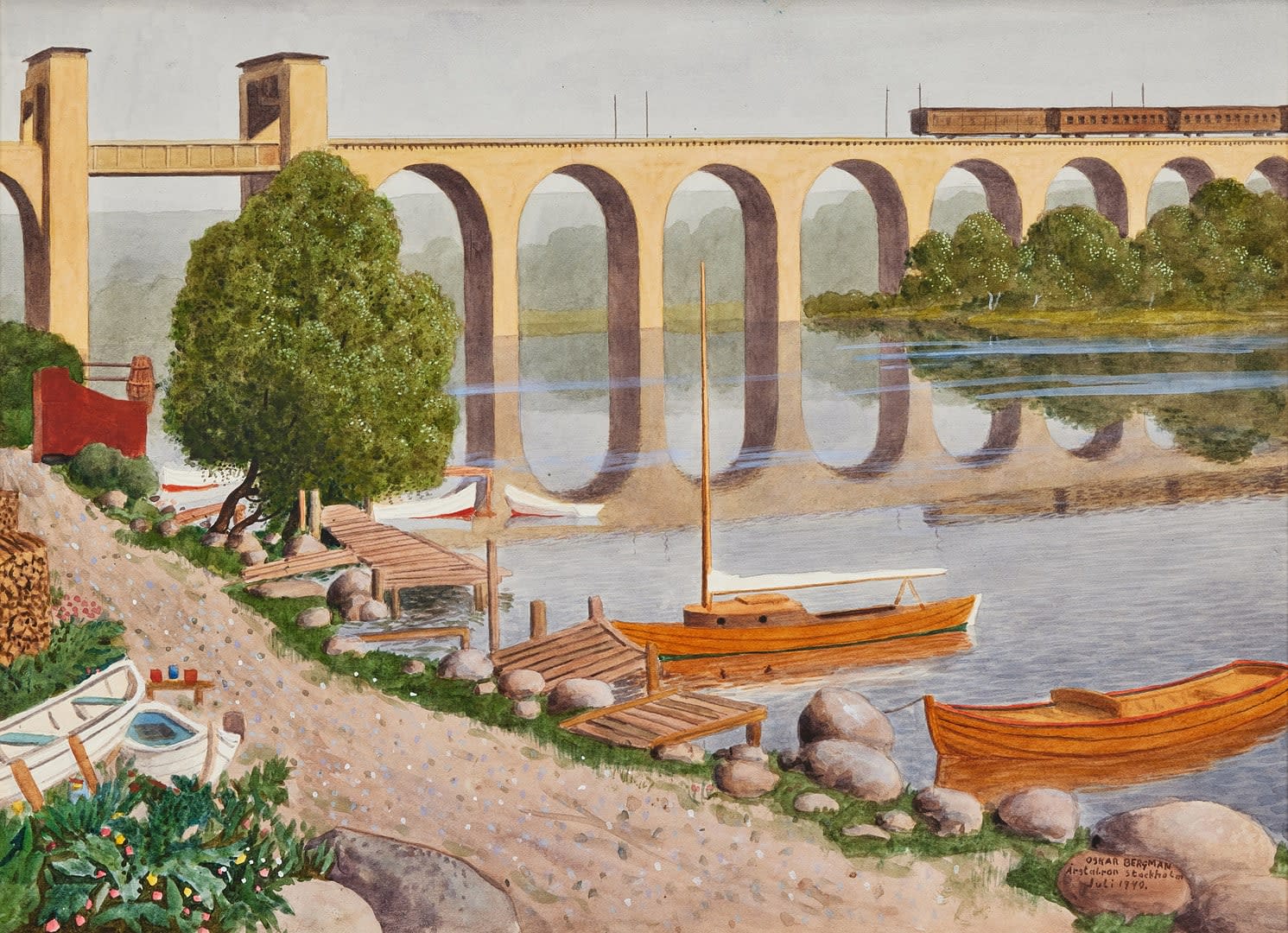

Oscar Bergman

Årsta Bridge, Stockholm, July 1940

Watercolour and gouache on card

36.5 x 51 cm

14 3/8 x 20 1/8 in

14 3/8 x 20 1/8 in

Copyright The Artist

Painted and inscribed July 1940, this luminous view looks across Årstaviken to the long arcade of Årstabron—the older (eastern) Årsta railway viaduct, opened in 1929 as part of Stockholm’s modern...

Painted and inscribed July 1940, this luminous view looks across Årstaviken to the long arcade of Årstabron—the older (eastern) Årsta railway viaduct, opened in 1929 as part of Stockholm’s modern rail infrastructure. Stretching roughly 753 metres, the bridge was designed by architect Cyrillus Johansson with engineers Ernst Nilsson and Salomon Kasarnowsky, and it has often been likened to a classical Roman aqueduct—an analogy Oscar Bergman underscores through the steady rhythm of arches mirrored in the still water.

Bergman animates the monumental structure with a passing train, but the emotional centre is closer to shore: jetties, small boats pulled up on sunlit stones, and a quiet working waterfront. The composition is typical of his gift for balancing precise observation with atmosphere—here, the sober permanence of engineering becomes a serene stage-set for everyday summer life.

Although widely admired for landscapes and the Nordic motif, Bergman was also a deeply Stockholm-based painter, repeatedly returning to city viewpoints and waterside thresholds where built form and nature meet. Born and working largely in Stockholm, he is often described as an autodidact despite studies at Tekniska aftonskolan (Konstfack) and subsequent study travel in Europe; he maintained a naturalist clarity even as newer, non-figurative ideals gained ground.

Alongside the birch woods, roads, and archipelago motifs for which he is best loved, Bergman repeatedly returned to Stockholm’s most recognisable silhouettes—using architecture as a steady “anchor” for atmosphere and season. He painted viewpoints over Riddarhuset (the House of Nobility) and the historic island skyline crowned by Riddarholmskyrkan, often letting the city’s stone landmarks emerge through humid light or dusk-tones with the same sensitivity he brought to countryside views. He was equally drawn to Södermalm’s emblematic profile, including compositions featuring Katarina kyrka, where the dome rises above the older wooden quarters, and he made distinct, documentary-poetic studies of working waterfronts such as Stadsgården, where quays, boats, and the rhythm of the city meet the water. Djurgården also appears as a recurring setting in his Stockholm imagery, not least in works that take Rosendal as a motif—evidence of how naturally he moved between parkland, palace architecture, and waterside life within the same quiet, observational register. When he worked beyond the capital, he could treat built heritage in much the same way: for example, he painted Visby ringmur on Gotland, approaching the medieval wall less as a “monument” than as a living edge within landscape and weather.

Bergman is often described as largely self-taught. Instead of a conventional Academy path, he trained through Tekniska skolans evening courses (from 1896 to 1900) and developed his skills through sustained self-study; his drawing teacher there was Anders Forsberg. This practical route—close to craft, illustration, and working life—remained part of his artistic DNA, and helps explain the almost “worked” clarity of his surfaces, whether he is recording a shoreline, a stand of birch trees, or the geometry of a city view.

A crucial early factor in Bergman’s career was the support of his patrons Signe Maria and Ernest Thiel, who not only acquired his works but also offered him board and lodging at their Neglinge artist home in Saltsjöbaden around 1900—support that proved decisive at the beginning of his professional life. Through the Thiel sphere, and through his own travels, Bergman’s horizons widened further: a notable episode was his journey to Florence in 1905, enabled by Thiel’s financing, where he encountered the Symbolist milieu around Armand Point and chose, characteristically, to work with a strong independent streak even when institutional or pedagogical frameworks were available.

Bergman’s public profile rose and fell over the decades, but key milestones include exhibiting at Liljevalchs (1929), a sequence of shows at Galerie Moderne (from 1931 onward), and the renewed attention brought by retrospectives in 1939 and 1940, after which his watercolours—especially birch motifs, winter scenes, and Stockholm views—found a wide audience. Later highlights include a solo exhibition at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in 1953, and in 1957 he received the Egron Lundgren Medal (a major Swedish distinction for watercolourists).

Painted and inscribed July 1940, this luminous view looks across Årstaviken to the long arcade of Årstabron—the older (eastern) Årsta railway viaduct, opened in 1929 as part of Stockholm’s modern rail infrastructure. Stretching roughly 753 metres, the bridge was designed by architect Cyrillus Johansson with engineers Ernst Nilsson and Salomon Kasarnowsky, and it has often been likened to a classical Roman aqueduct—an analogy Oscar Bergman underscores through the steady rhythm of arches mirrored in the still water.

Bergman animates the monumental structure with a passing train, but the emotional centre is closer to shore: jetties, small boats pulled up on sunlit stones, and a quiet working waterfront. The composition is typical of his gift for balancing precise observation with atmosphere—here, the sober permanence of engineering becomes a serene stage-set for everyday summer life.

Although widely admired for landscapes and Nordic motifs, Bergman was also firmly a Stockholm-based painter, repeatedly returning to city viewpoints and waterside thresholds where built form and nature meet. Born and working largely in Stockholm, he is often described as an autodidact despite studies at Tekniska aftonskolan (Konstfack) and subsequent study travel in Europe; he maintained a naturalist clarity even as newer, non-figurative ideals gained ground.

Alongside the birch woods, roads, and archipelago views for which he is best loved, Bergman repeatedly returned to Stockholm’s most recognisable silhouettes—using architecture as a steady “anchor” for atmosphere and season. He painted viewpoints over Riddarhuset (the House of Nobility) and the historic island skyline crowned by Riddarholmskyrkan, often letting the city’s stone landmarks emerge through humid light or dusk-tones with the same sensitivity he brought to countryside views. He was equally drawn to Södermalm’s emblematic architecture, including compositions featuring Katarina Church, where the dome rises above the older wooden quarters, and he made distinct, documentary-poetic studies of working waterfronts such as Stadsgården, where quays, boats, and the rhythm of the city meet the water. Djurgården also appears as a recurring setting in his Stockholm imagery, not least in works that take Rosendal as a motif—evidence of how naturally he moved between parkland, palace architecture, and waterside life within the same quiet, observational register. When he worked beyond the capital, he would treat built heritage in much the same way: for example, he painted Visby ringmur on Gotland, approaching the medieval wall less as a “monument” than as a living edge within landscape and weather.

A crucial early factor in Bergman’s career was the support of his patrons Signe Maria and Ernest Thiel, who not only acquired his works but also offered him board and lodging at their Neglinge artist home in Saltsjöbaden around 1900—support that proved decisive at the beginning of his professional life. Through the Thiel sphere, and through his own travels, Bergman’s horizons widened further: a notable episode was his journey to Florence in 1905, enabled by Thiel’s financing, where he encountered the Symbolist milieu around Armand Point and chose, characteristically, to work with a strong independent streak even when institutional or pedagogical frameworks were available.

Bergman’s public profile rose and fell over the decades, but key milestones include exhibiting at Liljevalchs (1929), a sequence of shows at Galerie Moderne (from 1931 onward), and the renewed attention brought by retrospectives in 1939 and 1940, after which his watercolours—especially birch motifs, winter scenes, and Stockholm views—found a wide audience. Later highlights include a solo exhibition at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in 1953, and in 1957 he received the Egron Lundgren Medal (a major Swedish distinction for watercolourists).

Bergman animates the monumental structure with a passing train, but the emotional centre is closer to shore: jetties, small boats pulled up on sunlit stones, and a quiet working waterfront. The composition is typical of his gift for balancing precise observation with atmosphere—here, the sober permanence of engineering becomes a serene stage-set for everyday summer life.

Although widely admired for landscapes and the Nordic motif, Bergman was also a deeply Stockholm-based painter, repeatedly returning to city viewpoints and waterside thresholds where built form and nature meet. Born and working largely in Stockholm, he is often described as an autodidact despite studies at Tekniska aftonskolan (Konstfack) and subsequent study travel in Europe; he maintained a naturalist clarity even as newer, non-figurative ideals gained ground.

Alongside the birch woods, roads, and archipelago motifs for which he is best loved, Bergman repeatedly returned to Stockholm’s most recognisable silhouettes—using architecture as a steady “anchor” for atmosphere and season. He painted viewpoints over Riddarhuset (the House of Nobility) and the historic island skyline crowned by Riddarholmskyrkan, often letting the city’s stone landmarks emerge through humid light or dusk-tones with the same sensitivity he brought to countryside views. He was equally drawn to Södermalm’s emblematic profile, including compositions featuring Katarina kyrka, where the dome rises above the older wooden quarters, and he made distinct, documentary-poetic studies of working waterfronts such as Stadsgården, where quays, boats, and the rhythm of the city meet the water. Djurgården also appears as a recurring setting in his Stockholm imagery, not least in works that take Rosendal as a motif—evidence of how naturally he moved between parkland, palace architecture, and waterside life within the same quiet, observational register. When he worked beyond the capital, he could treat built heritage in much the same way: for example, he painted Visby ringmur on Gotland, approaching the medieval wall less as a “monument” than as a living edge within landscape and weather.

Bergman is often described as largely self-taught. Instead of a conventional Academy path, he trained through Tekniska skolans evening courses (from 1896 to 1900) and developed his skills through sustained self-study; his drawing teacher there was Anders Forsberg. This practical route—close to craft, illustration, and working life—remained part of his artistic DNA, and helps explain the almost “worked” clarity of his surfaces, whether he is recording a shoreline, a stand of birch trees, or the geometry of a city view.

A crucial early factor in Bergman’s career was the support of his patrons Signe Maria and Ernest Thiel, who not only acquired his works but also offered him board and lodging at their Neglinge artist home in Saltsjöbaden around 1900—support that proved decisive at the beginning of his professional life. Through the Thiel sphere, and through his own travels, Bergman’s horizons widened further: a notable episode was his journey to Florence in 1905, enabled by Thiel’s financing, where he encountered the Symbolist milieu around Armand Point and chose, characteristically, to work with a strong independent streak even when institutional or pedagogical frameworks were available.

Bergman’s public profile rose and fell over the decades, but key milestones include exhibiting at Liljevalchs (1929), a sequence of shows at Galerie Moderne (from 1931 onward), and the renewed attention brought by retrospectives in 1939 and 1940, after which his watercolours—especially birch motifs, winter scenes, and Stockholm views—found a wide audience. Later highlights include a solo exhibition at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in 1953, and in 1957 he received the Egron Lundgren Medal (a major Swedish distinction for watercolourists).

Painted and inscribed July 1940, this luminous view looks across Årstaviken to the long arcade of Årstabron—the older (eastern) Årsta railway viaduct, opened in 1929 as part of Stockholm’s modern rail infrastructure. Stretching roughly 753 metres, the bridge was designed by architect Cyrillus Johansson with engineers Ernst Nilsson and Salomon Kasarnowsky, and it has often been likened to a classical Roman aqueduct—an analogy Oscar Bergman underscores through the steady rhythm of arches mirrored in the still water.

Bergman animates the monumental structure with a passing train, but the emotional centre is closer to shore: jetties, small boats pulled up on sunlit stones, and a quiet working waterfront. The composition is typical of his gift for balancing precise observation with atmosphere—here, the sober permanence of engineering becomes a serene stage-set for everyday summer life.

Although widely admired for landscapes and Nordic motifs, Bergman was also firmly a Stockholm-based painter, repeatedly returning to city viewpoints and waterside thresholds where built form and nature meet. Born and working largely in Stockholm, he is often described as an autodidact despite studies at Tekniska aftonskolan (Konstfack) and subsequent study travel in Europe; he maintained a naturalist clarity even as newer, non-figurative ideals gained ground.

Alongside the birch woods, roads, and archipelago views for which he is best loved, Bergman repeatedly returned to Stockholm’s most recognisable silhouettes—using architecture as a steady “anchor” for atmosphere and season. He painted viewpoints over Riddarhuset (the House of Nobility) and the historic island skyline crowned by Riddarholmskyrkan, often letting the city’s stone landmarks emerge through humid light or dusk-tones with the same sensitivity he brought to countryside views. He was equally drawn to Södermalm’s emblematic architecture, including compositions featuring Katarina Church, where the dome rises above the older wooden quarters, and he made distinct, documentary-poetic studies of working waterfronts such as Stadsgården, where quays, boats, and the rhythm of the city meet the water. Djurgården also appears as a recurring setting in his Stockholm imagery, not least in works that take Rosendal as a motif—evidence of how naturally he moved between parkland, palace architecture, and waterside life within the same quiet, observational register. When he worked beyond the capital, he would treat built heritage in much the same way: for example, he painted Visby ringmur on Gotland, approaching the medieval wall less as a “monument” than as a living edge within landscape and weather.

A crucial early factor in Bergman’s career was the support of his patrons Signe Maria and Ernest Thiel, who not only acquired his works but also offered him board and lodging at their Neglinge artist home in Saltsjöbaden around 1900—support that proved decisive at the beginning of his professional life. Through the Thiel sphere, and through his own travels, Bergman’s horizons widened further: a notable episode was his journey to Florence in 1905, enabled by Thiel’s financing, where he encountered the Symbolist milieu around Armand Point and chose, characteristically, to work with a strong independent streak even when institutional or pedagogical frameworks were available.

Bergman’s public profile rose and fell over the decades, but key milestones include exhibiting at Liljevalchs (1929), a sequence of shows at Galerie Moderne (from 1931 onward), and the renewed attention brought by retrospectives in 1939 and 1940, after which his watercolours—especially birch motifs, winter scenes, and Stockholm views—found a wide audience. Later highlights include a solo exhibition at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in 1953, and in 1957 he received the Egron Lundgren Medal (a major Swedish distinction for watercolourists).

Provenance

Descendants of the artist;Their sale, Stockholms Auktionsverk, September 2025, Lot 361;

Where acquired

Exhibitions

Sveagalleriet, Sveavägen, Stockholm, "Stockholm från Söder" exhibition, cat no 10 (according to old label);Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm, "Stilla Natur", February-August 2023, cat no 62

Literature

Åsa Cavalli Björkman (ed), "Stilla Natur", Thielska Galleriet, Exhibition catalogue, 2023, illustrated p. 441

of

439